Following Jane Austen’s literary triumph in the Georgian Era, the ensuing Victorian Era saw the emergence of phenomenal works from female writers such as George Eliot (real name Maryanne Evans) and the Bronte sisters: Charlotte, Emily, and Anne. Although many scholars and academics question the gender based difference, if any, between male and female styles of writing during the period, this paper is concerned with analysing how stylistically similar the Bronte sisters are in their individually accomplished works. This paper will outline the results of a series of quantitative analyses focused on the collective corpus of Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Bronte, both on its own and as part of a wider analysis that includes the corpus of George Eliot and Jane Austen, followed by some literary interpretations.

The Bronte sisters have long been celebrated on their own merits for their individually accomplished works; both Charlotte’s Jane Eyre and Emily’s Wuthering Heights remain at the centre of the English literary canon while Anne’s lesser known but equally great The Tenant of Wildfell Hall is now held up by critics as the first sustained feminist novel. Although the sisters are separately acclaimed novelists some academic criticism has been focused on drawing comparisons between their works. Critic N.M. Jacobs acknowledges the similarities between The Tenant of Wildfell Hall and Wuthering Heights in relation to gender and layered narrative. While Jacobs notes that all three of the Bronte sisters explore the theme of gender and gender roles in their novels she outlines their different approaches. Jacobs considers Anne and Emily’s approach to be similar and only differing in intensity and overtness while she accuses the eldest Bronte, Charlotte, of eroticizing the dominant/submissive dynamic of gender relations in her novels (Jacobs, 1986). Critic Laura Berry also discusses the narrative similarities between Wuthering Heights and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, particularly arguing that the acts of marriage are replaced by acts of custody and incarceration in the novels in order for both Anne and Emily to explore the concerns of domesticity during the 19th century period (Berry, 1996). Other critics such as Jacqueline Simpson illustrate the similarity between Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights where folklore and folk belief are prominent in both works (Simpson, 1974).

Although some comparative criticism exists on the Bronte sisters this paper offers a precise and unique stylistic comparison on their collective corpus. Through the implementation of quantitative methods and computational stylistics relevant passages are precisely selected and focused on for literary analysis.

Methodology and Results

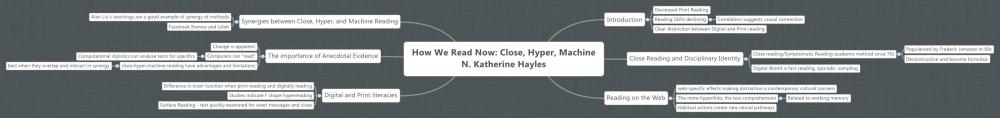

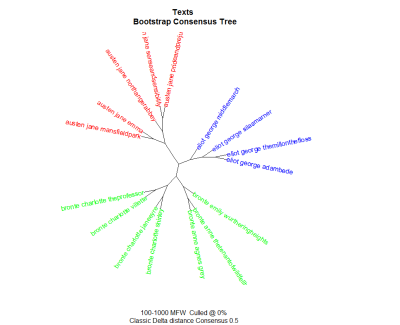

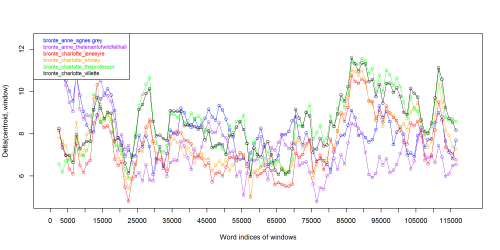

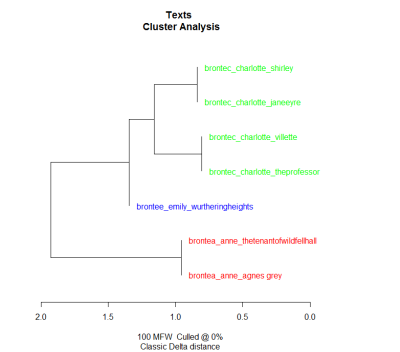

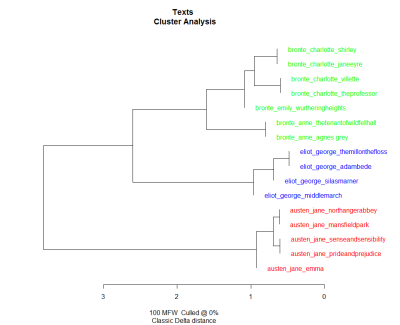

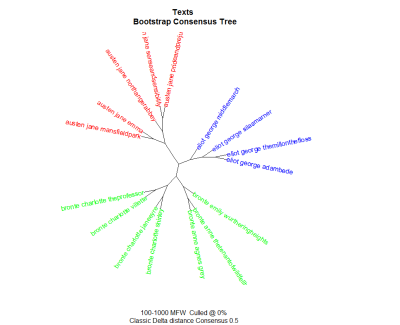

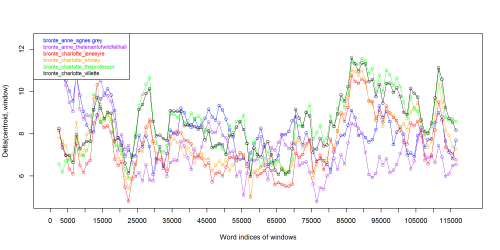

Using the software R and R package “stylo” (Eder et al., 2013) a number of multivariate stylometric methods where used to analyse the Bronte corpus in this study. An initial cluster analysis of the Bronte sister’s collective corpus provided a preliminary insight into a comparison of their style based on the one hundred most frequent words. Following this, another cluster analysis was conducted featuring the corpus of Jane Austen and George Eliot, two other noted 19th century female authors, in order to provide a more comprehensive analysis of stylistic similarities. Owing to the intriguing results found in the cluster analysis of the 19th century female writers a more robust analysis was conducted by generating a Bootstrap Consensus Tree of the same corpus. As opposed to analysing the one hundred most frequent words, as the cluster analysis does, the Bootstrap Consensus Tree analyses the texts by the thousand most frequent words which provides a more extensive investigation of stylistic similarities. Finally, in order to identify relevant passages for literary interpretation a Rolling Delta (Rybicki et al., 2013) analysis was carried out on the Bronte sister’s corpus. The Rolling Delta determines an identifiable authorial signature based on one of the texts provided and then compares all other texts provided to the aforementioned authorial style in order to determine stylistic similarities at precise sections of the texts. For this study, Emily’s only novel Wuthering Heights was used as the authorial baseline for the Rolling Delta analysis and all of Charlotte’s and Anne’s novels were compared to it to determine the relevant sections of similarity.

Initially, the following novels where put through R in a cluster analysis:

- Emily Bronte. Wuthering Heights (1847)

- Charlotte Bronte. The Professor (Published in 1857 but written before Jane Eyre)

- Charlotte Bronte. Jane Eyre (1847)

- Charlotte Bronte. Shirley (1849)

- Charlotte Bronte. Villette (1853)

- Anne Bronte. Agnes Grey (1846)

- Anne Bronte. The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848)

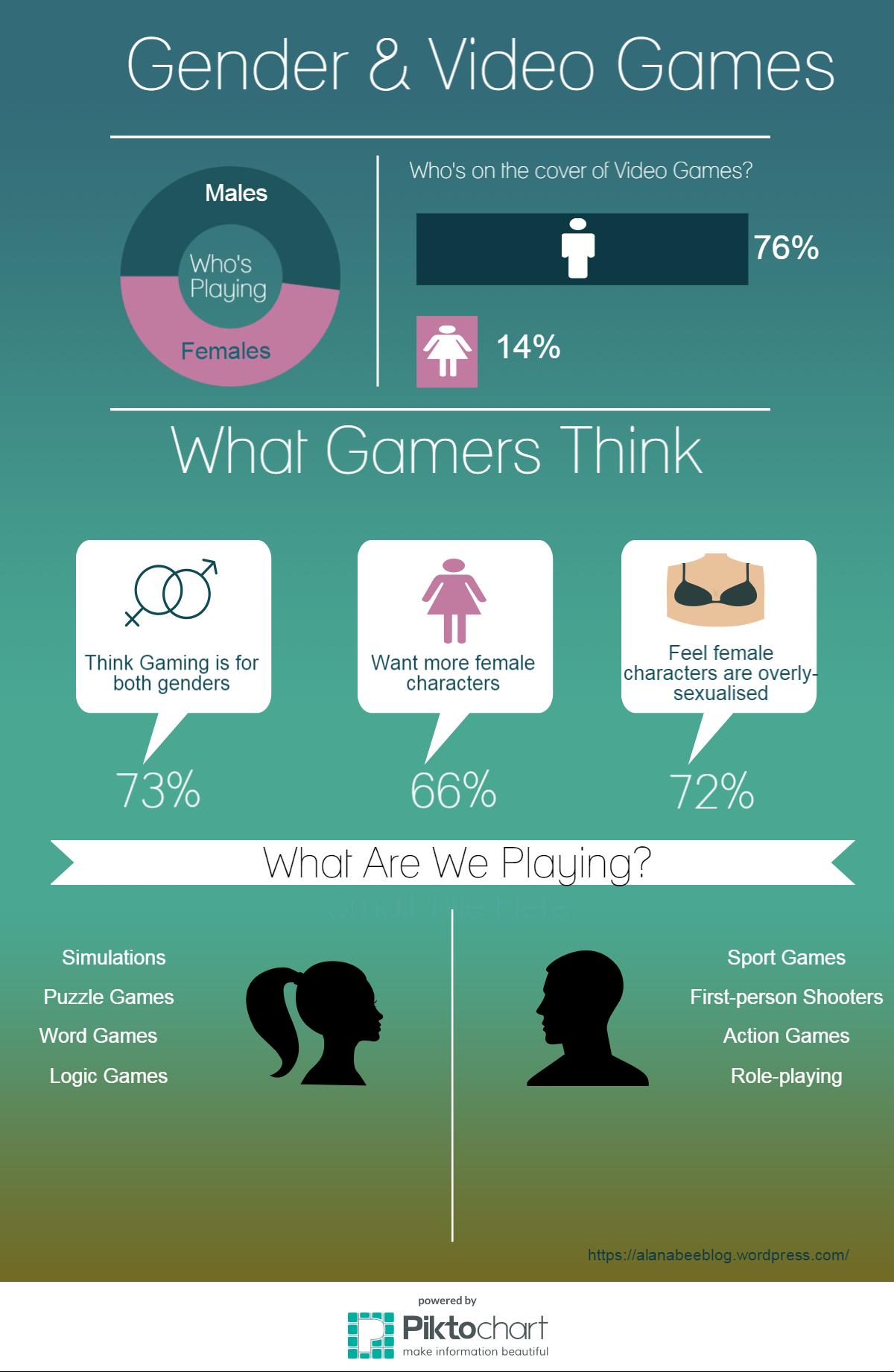

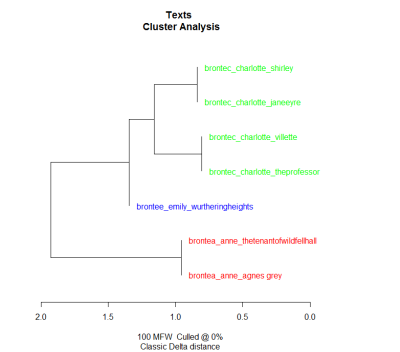

The cluster analysis produced the following results:

The computational analysis successfully clustered the novels together according to the specific Bronte sister who wrote them thereby indicating the unique authorial style of each writer; Charlotte Bronte’s four novels appear together in green, Emily’s only novel in Blue, and Anne Bronte’s novels in red.

As previously mentioned, other noted 19th century female authors were considered in order to compare them to the Bronte sister’s collective corpus for a more comprehensive stylistic analysis. A selection of Jane Austen’s novels and all of George Eliot’s known novels, both of whom published in the 19th century, were added to the list of texts to be assessed for style. In addition to the Bronte collection, the second Cluster Analysis conducted for the purposes of this study included the following novels:

- Jane Austen. Emma (1815)

- Jane Austen. Sense and sensibility (1811)

- Jane Austen. Northanger Abbey (1818)

- Jane Austen. Pride and Prejudice (1813)

- Jane Austen. Mansfield Park (1814)

- George Eliot. Adam Bede (1859)

- George Eliot. Middlemarch (1871/72)

- George Eliot. Silas Marner (1861)

- George Eliot. The Mill on the Floss (1860)

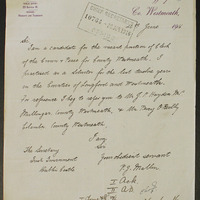

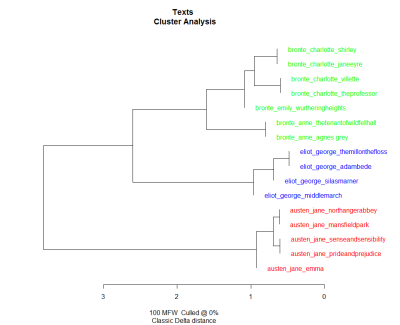

The inclusion of fellow 19th century female authors had a considerable effect on the results of the Cluster Analysis. Jane Austen’s novels cluster together in red, George Eliot’s novels in blue and the Bronte’s in green. The software clusters the Bronte sisters together indicating a notably similar style within their collective corpus. A more robust Bootstrap Consensus Tree of the same collection of novels provides similar results:

Austen’s work branches off from the other authors indicating her renowned unique style of writing and a prominent authorial signature within her work. Austen’s work splits into subsequent branches illustrating her distinct style in use within various genres and allowing for a progression in authorial style over time. Similarly, George Eliot’s work assembles as a collection very similar in style, demonstrating an individual authorial signature is also prominent within her work. The Brontes, however, cluster together and appear almost like a singular author with malleable style rather than three separate authors with a distinct style. Moreover, the data indicates a marked similarity between Anne Bronte and Emily Bronte’s style.

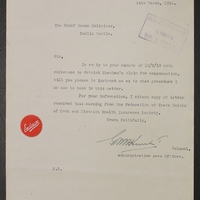

As both the Cluster Analysis and the Bootstrap Consensus Tree confirm a striking similarity in style between the three Bronte sisters, particularly Emily and Anne Bronte, a Rolling Delta was carried out in order to locate specific sections of the novels where a marked correlation in style occurs. As previously mentioned, Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights was implemented as the baseline text to which all of Charlotte and Anne’s novels were compared:

As evidenced above, there are a number of incidences where the Bronte sister’s authorial style correlates. Jane Eyre appears to have a distinct similarity to specific sections of Wuthering Heights. Moreover, Anne Bronte’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall appears most consistently stylometrically similar to Wuthering Heights particularly in the latter half of the text which confirms the original Cluster Analysis and Bootstrap Consensus results.

Literary Interpretations

The results of the stylometric analysis offer a significant contribution to limited existing comparative scholarship on the Bronte sisters, particularly the scholarship focused on the comparisons drawn between Anne and Emily Bronte’s work. Below is a literary interpretation specifically focused on the correlations between Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights and Anne Bronte’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall as outlined by the results of the computational analyses.

As previously mentioned, the Rolling Delta analysis indicated a marked stylistic similarity between specific sections of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall and Wuthering Heights. Although the novels are distinctly different both in theme and genre, Wuthering Heights is considered a work gothic fiction while The Tenant of Wildfell Hall is considered to be a work of social criticism, there are a number of reasons for the stylistic similarities.

Interestingly, the shared biographical details of both sisters account for a considerable similarity in their authorial style. Aside from a shared genetic predisposition the Bronte sisters also shared a childhood environment and had access to the same reading materials. Numerous biographies account the close relationship Anne and Emily shared. As children both Anne and Emily created a complex imaginary world they called Gondal in which they created characters and acted out narratives and poetry together centred on this imaginary world (Fraser, 1988). The creation of narratives together as children created a stylistic framework from which the sisters would draw on later in life when they began their independent narratives. Moreover, both Anne and Emily adopted shared biographical details and implemented them in their respective novels. The settings for both Wuthering Heights and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall are adapted from the Yorkshire moors where the sisters grew up. Numerous passages in the novels are devoted to descriptions of the rich countryside landscapes that the sisters shared an experiential familiarity with. Furthermore, Emily and Anne chose to chronicle their experience with their older brother Branwell Bronte in their respective novels. Branwell suffered a steady and violent decline into alcohol and opiate addiction which the sisters were witness to. Both Emily and Anne went on to expose the destructive nature of addiction through the characters Hindley Earnshaw in Wuthering Heights and the vicious character of Arthur Huntington in The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, both of whom drink themselves to death. Through the Branwell based characters “each book depicts an unpleasant and often violent domestic reality” (Jacobs, 1986). Owing to the influence of biographical details the novels, although markedly different, appear to have a considerable correlation in authorial style. The influence of biography explains the aforementioned correlation as both novels touch on similar issues which the sisters write about from a mutual experience.

Additionally, both The Tenant of Wildfell Hall and Wuthering Heights share a similar narrative framework. Wuthering Heights employs an internal male narrator who writes the narrative as an entry in his diary, the details of which are recalled to him by the female character Nelly. Similarly The Tenant of Wildfell Hall utilizes an internal male narrator who writes the narrative as a letter, however, within the letter are the diary entries of the female protagonist Helen Graham. Critics argue that the male narrator represents the public ideologies of the time while the female narrators within the frameworks give access to the “pervasively violent private reality” (Jacobs, 1986). Intriguingly, the precise sections of significant similarities in authorial style within the novels, as indicated by the Rolling Delta, are sections told through the perspective and experience of the female characters. The select passages from The Tenant of Wildfell Hall are the sections of Helen Graham’s diaries in which she catalogues the decline of her marriage, her tyrannical husband’s deplorable behaviour, his humiliation of her, and the effect this has on her. Both the Tenant of Wildfell Hall and Wuthering Heights resolve the violent domestic worlds at the end of the narratives; the novels end in harmonious marriages where the characters enjoy happier domestic lives which accounts for the similarities in the latter half of the novels indicated by the Rolling Delta analysis.

Although the Bronte sisters are celebrated as individuals for their independently accomplished works, stylometric evidence suggests a much closer correlation in style than previously thought. Closer reading and literary analysis advocates this correlation in style and suggests that although the sisters wrote in different genres and explored different themes their authorial style remains incredibly similar.

Works Cited

Berry, Laura C. “Acts of Custody and Incarceration in “Wuthering Heights” and “The Tenant of Wildfell Hall”” NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction 30.1 (1996): 32-55. Print.

Brontë, Anne. The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1979. Print.

Brontë, Emily. Wuthering Heights. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1996. Print.

Eder, Maciej, Mike Kestemont, and Jan Rybicki. “Stylometry with R: A Suite of Tools.”Digital Humanities 2013: Conference Abstracts (2013): 487-89. Web. 06 Dec. 2013.

Fraser, Rebecca. The Brontës: Charlotte Brontë and Her Family. New York: Crown, 1988. Print.

Jacobs, N. M. “Gender and Layered Narrative in “Wuthering Heights” and “The Tenant of Wildfell Hall”” The Journal of Narrative Technique 16.3 (1986): 204-19. Print.

Rybicki, Jan, Mike Kestemont, and D. L. Hoover. “Collaborative Authorship: Conrad, Ford and Rolling Delta.” Digital Humanities 2013: Conference Abstracts (2013): 368-71. Web. 06 Dec. 2013.

Simpson, Jacqueline. “The Function of Folklore in ‘Jane Eyre’ and ‘Wuthering Heights'” Folklore 85.1 (1974): 47-61. JSTOR. Web. 06 Dec. 2013.